Part 2

How Does User Testing Work?

"Walk a hundred steps in somebody else's shoes, if you want to understand them." -- Ancient proverb

First Steps...

After emphasizing in the previous part how easy it is to conduct user tests by yourself, let's prove the point in the second part of this book. For this purpose, we'll go through the entire process step by step and tell you everything you need to know, so that you or your team can continually improve your product with the help of user testing.

The individual steps of this process, which we'll introduce in more detail in the following chapters, are the following:

- Selection of the test tasks

- Creation of the test scenario

- Finding test participants

- Conducting the tests

- Assessing the tests

- Sharing of the test results

- Further testing

We'll explain what we do in each step, how we do it and of course also why we do it the way we do it. As you'll notice, the reason we do something in a certain way is because we want user testing to really work in practice. Thus, on the following pages you won't find any unrealistic descriptions of best practices (which in practice anyway no one actually uses), but rather a realistic approach, tested in practice, easily integrated into any development process.

We've also come to the conclusion that what works best is to go through the whole process with a hands-on example, so that you can use this example to figure out how to apply each step to your own product.

Finally, as a practical example, we have chosen Pawshake -- an online animal care platform -- to show you step by step how we conducted user testing on this platform.

www.pawshake.de screenshot

If you're wondering why we chose Pawshake: Well, we were looking for a product not already known to everybody (because that would be boring) but immediately understood by any person reading this book (because otherwise it would be unnecessarily complicated). And since we found the idea of Pawshake somehow interesting, and the process we describe in this book can be applied to any kind of product anyway, Pawshake is as good as any other website or app (or whatever product) we could have chosen.

Are you ready? Here we go!

Selection of the Test Tasks

It's simply not enough just to show people a product to find out what its usability problems are. You have to give them concrete and realistic tasks and observe them while they are trying to do these tasks.

Thus, the first thing to do is to create a list of tasks for the users of a product, select the most important tasks for the first round of testing, and turn those tasks into realistic test scenarios in the next step.

Don't worry, we'll show you how this works step-by-step, using our example web page. If we look at Pawshake's web page, we can see some things users can do there:

- Find a pet sitter

- Compare pet sitters

- Contact a pet sitter

- Book a pet sitter

- Rate a pet sitter

- Add a pet sitter as a favorite

- Read a blog article

- Contact Pawshake

Create Your Own Task List

Now think about what users do on your own website or with your product and make a list, as in our example. Don't waste your time with details, just write down everything that comes to your mind and don't get lost in finding the perfect descriptions for your tasks. The best would be to include your team in this process.

You should draw up a list of five to ten tasks. Checking all your tasks in a single round of testing wouldn't only take too long, but the test would also be very unrealistic. After all, hardly anybody will find a pet sitter, arrange for care, rate the pet sitter, send and receive messages, and even enroll as a pet sitter during a single visit to Pawshake. Thus, we should decide which tasks we should start our first round of testing with.

Select the Most Important Tasks

Have you ever been to London? Maybe you've noticed the red lines marked on the streets there. Streets marked with these lines are called "Red Routes". An absolute parking and stopping prohibition applies there -- not even getting in or out of a car is allowed. The reason for this is that these lines mark the main traffic nodes and it's in the city's best interest to keep the traffic there as fluid as possible. These Red Routes must be kept free; otherwise there will be problems throughout the entire city. Your product also has these main routes, even if you haven't set them up intentionally.

These are the Red Routes of some well-known websites:

- Amazon: Purchase a product

- Uber: Order a car (as a customer) or accept a ride (as a driver)

- Airbnb: Book a place to stay

- YouTube: Watch a video

What role do Red Routes play in our user tests? The idea of this book is to show you how to improve your product through user testing, investing as little time and money as possible. For this reason, we can't test everything at the same time -- it would be far too costly and, as already mentioned, also unrealistic.

During our first round of testing, we'll focus on areas of our product where even minor usability problems can have a big impact. Because even the best usability of your messaging feature will give you precious little results if none of your users ever sends you a message. For this reason, we'll start our user tests with the Red Routes of your product.

The Red Routes of your product are:

- Used by many: Tasks performed by most of your users.

- Used frequently: Tasks performed by individual users during almost every interaction.

Here's a little help if you're having a hard time deciding which tasks are the Red Routes of your website: Go through each individual task on your list and award three points for tasks your users perform on almost every interaction with your product, two points for tasks your users perform only occasionally, and one point for tasks only rarely performed by your users. You can also award the points together with your team and independently of each other. At the end, just sum up your points and start the first round of testing with the three tasks with the highest number of points.

Pawshake's Red Routes

Let's get back to our example. Which might be the main traffic route of Pawshake's website?

- Find a pet sitter

- Compare pet sitters

- Contact a pet sitter

- Book a pet sitter

- Rate a pet sitter

- Add a pet sitter as a favorite

- Read a blog article

- Contact Pawshake

Pawshake's website is mostly about this: Finding a suitable pet sitter and book him/her through the site. Thus, the three most important tasks of this website are:

- Find a pet sitter

- Compare pet sitters

- Book a pet sitter

The order of these tasks also sounds reasonable, because before booking a pet sitter, you must first find one and most probably, you'll wish to compare several pet sitters.

Have you discovered the Red Routes of your product and chosen the three most important tasks for your first round of testing? Perfect, in the next step we will use these tasks for a specific and realistic process for our user test.

Creation of the Test Scenario

The tasks for your user tests should be as clear as possible and, at the same time, influence your test participants as little as possible. This is achieved by means of a test scenario.

A test scenario includes all test tasks to be performed by our test participants. But before we assign these tasks, we'll give our testers two more things along the way: an explanation as realistic as possible of the situation in which they should put themselves and a plausible reason to use our product.

We'll use Pawshake's tasks, created in the previous chapter, to show you how to do this:

- Find a pet sitter

- Compare pet sitters

- Book a pet sitter

If we use these three tasks literally for our test, it sounds like this:

Bad: Find a pet sitter, compare some pet sitters to each other

and then book one.

We can't simply ask our test participants to "find a pet sitter" -- there's no explanation at all why they should do this. Should the test participants find a pet sitter for themselves or for somebody else? Are they in urgent need of a pet-sitter for tonight or are they planning to go on vacation and are looking for a longer stay for their pet? And what animal is it all about? A cat, a dog, a lizard? All these questions have an impact on the behavior of our test participants. And if we don't mention these details in our scenario, on the one hand, we are leaving what happens to chance, and on the other hand, our test participants will find it very difficult to put themselves in the position we need them to be in. If we want to observe a behavior as realistic as possible, we should be much more specific:

Better: Find possible pet sitters for your dog in your area,

compare some of them to each other and try to book a suitable

one for next weekend.

This task causes your test participants to behave more naturally on the website than if you simply ask them to "find a pet sitter". You're also indicating the specific kind of animal, a specific date and by asking them to find animal sitter in their area, your task becomes much more realistic. Thus, observing a natural behavior and real usability problems becomes much more likely. What is still missing is an explanation of why our test participants are looking for a pet sitter for their dog. We accomplish this by explaining more about the situation in which we want them to use Pawshake:

Good: Imagine that you're going to a concert in the neighboring

town next Saturday and that you won't be back home until Sunday

evening. For this reason you're looking for somebody to take care

of your dog during this time.

This is something usually done by a friend, but this weekend she

has no time. However, she has told you about Pawshake and said

that you would find somebody there to take care of your dog.

Try to find a few candidates on this website to whom you would

entrust your dog during this time and compare them to each other.

Then choose your favorite and briefly explain your decision.

This task already has a lot of what is necessary for a good user test. Instead of asking them vaguely to "find a pet sitter", in addition to giving our test participants specific time frame details (next Saturday), we're also giving them a plausible reason to hire a pet sitter (the friend has no time) and a brief explanation of the context (the concert and the night spent in the neighboring city) to interact with the website.

A good test scenario should necessarily include these three things:

- Context: A description of the situation in which the product is used.

- Motivation: A plausible reason to use your product.

- Tasks: Several, as specific as possible tasks.

The first part of our test scenario is now ready. In our user test of Pawshake, we not only want to learn which usability problems there are in finding a pet sitter, but also to test the booking process. Below is the task of our list which is still missing:

Bad: Book a pet sitter

By now you already know that we can't assign this task as it has no context. Incidentally, we're also using the words displayed on the big button on Pawshake's homepage -- "Book Now". This is not optimal, because our test participants will turn on their tunnel vision and look for exactly those words on the website, turning our task into a word-search game and causing us to observe many less usability problems because we're over-influencing our participants. Thus, we should rewrite the task and avoid the words "book" and "pet sitter" as they appear on the page in exactly the same way.

Better: Now you want the person you've decided should take care

of your dog, to do so next weekend.

We've also made sure that our task fits the previous one -- we've finally asked our test participants to compare some of the pet sitters. The only information missing now is the moment our participants have reached their goal. In Pawshake's booking process, credit card details are also requested and we can't expect our testers to use their own credit card on the website. Especially as we record the entire screen and all the data entered. We'll therefore explain to them that the input of payment data is not necessary and when the test participants can consider their task as completed:

Good: Now you want the person you've decided should take care

of your dog, to do so next weekend. You can consider this task

as completed before entering payment details.

Perfect! Our test scenario is ready:

TASK 1:

Imagine that you're going to a concert in your neighboring town

next Saturday and that you won't be back home until Sunday

evening. Thus, you're looking for somebody to take care of your

dog during this time. This is something usually done by a friend,

but this weekend she has no time. However, she has told you about

Pawshake and said that you would find somebody there who will

take care of your dog.

Try to find a few candidates on this website to whom you would

entrust your dog during this time and compare them to each other.

Subsequently, choose your favorite and briefly explain your

decision.

TASK 2:

Now you want the person you've decided should take care of your

dog, to do so next weekend. You can consider this task as

completed before entering payment details.

Use these tips to turn your own tasks into test scenarios. If you find it hard to formulate your test scenarios -- don't worry! Since we're going to do several rounds of testing, your task doesn't need to be perfect yet. The user tests will also allow us to find out whether our test scenario is formulated in an intelligible manner and revise the scenario accordingly. We also test our testing procedure for usability, so to speak. In addition, in Part 3 you'll find many ready-made examples of tasks that you can apply to your test.

With our test scenario, we now have one of two things we need to start user testing for Pawshake. What is still missing, are suitable test participants, which we'll find in the next step.

Finding Test Participants

Once you have your test scenario, there's actually only one other thing you need now to start with the first tests: somebody you can test with. In this chapter, we'll explain who you should test with (and who not), how many test participants you need for your first round of testing, and where to find them.

The Myth of the Perfect Test Participant

As mentioned before, the only really big mistake you can make in user testing is not to start testing. However, this is something that often happens, when people wish to start their first tests and frantically try to find participants who are exactly the target group, because they fear that otherwise they'll get worthless test results due to having the wrong test participants. This plan ultimately fails, because in practice it's actually difficult to get the perfect test participant, so that many people not even start testing. This shouldn't strike us as something surprising, when requirements for test participants sound like this:

We are looking for people who meet our exact target group, i.e.

women between the ages of 18 and 29, single, living in the

metropolitan area of Graz or Vienna, with a gross income of at

least 50,000 € a year and with a degree in business administration.

These exact requirements concerning gender, age, income, occupation or place of residence are often determined by marketing managers. In marketing, the selection of the right demographic characteristics plays a major role -- reaching out to the right people with the advertising message ultimately determines the success of entire campaigns. But when doing user testing, we don't want to sell anything. What we do want is to discover usability problems by observing people's behavior. Thus, such demographic characteristics actually only play a very small role in our user tests:

"The importance of recruiting representative users is overrated." -- Steve Krug in "Don't Make Me Think!"

We won't necessarily get better results just because we've managed to find testers who have the exact demographic characteristics of our target group. Because, unlike, for example when doing surveys, we're not interested in the opinions of individuals; we're trying to understand their behavior to draw conclusions about usability problems. And the remarkable thing about human behavior is that different people behave similarly in similar situations. If the checkout button on your page is hidden, this will confuse somebody who fits your customer profile perfectly, just the same as it will somebody who isn't a potential customer, but has been given the task of shopping on your page.

The test participants in your user tests needn't match your exact target group. But there is an exception: products or services that require a high level of experience with a certain topic or a specific expertise. You'll find it difficult to test a UI for controlling a construction crane with somebody who has never operated a crane. But if you're not in the business of developing software for rocket scientists, something which requires that your users have specific knowledge of the subject and also some experience, it doesn't make much difference if the people you're testing with are part of your target group or not. Especially if your digital product is accessible to everybody on the Internet.

The search for test participants who perfectly match the profile only causes a greater effort and higher costs. Because even if we find a few participants who match our exact demographic characteristics, we'll always need new usability testers, as we're continually conducting tests. And finding new test participants from a very small target group is pure gambling and often ends with people stopping testing for lack of new participants. The perfect test participant doesn't exist -- so you shouldn't wait to find one or you'll never start testing.

How Many People Should You Test With

Imagine that you have a porcelain store. One day a piercing scream rings through the shop, followed closely by that feared sound of things breaking on the floor. When you get to the place, you find an elderly sad-faced lady in midst of a sea of broken pieces that once were your most exclusive tea set. You have somebody immediately remove the pile of broken fragments and start looking for the cause of this unfortunate event. You notice that the carpet has come loose in the immediate vicinity of the accident, creating a small wrinkle. You've never noticed this wrinkle before, and at first glance it actually appears to be rather inconspicuous. But apparently it was enough to make an older lady stumble. What can you do now?

Possibility No. 1: You have the carpet repaired and wait to see if after the repair another customer ends up in the same place in a sea of broken pieces.

Possibility No. 2: You wait to see if at least 36 other customers have the same accident so as to observe a representative number of cases and be able to say with statistical significance and absolute certainty, that there is indeed a problem.

The purpose of user testing is to observe the behavior of people who use your product, identify usability problems, fix them and thereby improve your product. As mentioned, we are not concerned with the opinions of individual persons, and therefore we don't need a statistically relevant number of test participants. In user testing (as in focus groups or interviews) we're dealing with a qualitative method (observing a behavior) and not with a quantitative method (collecting opinions). During user tests, we simply observe our test participants while using our product and try to identify the cause of the problems our product may have. And that's something usually quite easy, once we become aware of the problem.

Product teams often shy away from qualitative methods because they don't seem to be "sufficiently scientific". After all, a bar graph with percentages in a PowerPoint presentation looks a lot "truer" than referring to a single test participant who had problems in the most recent user test. But how much does quantitative data actually help you if your goal is to improve your product? If you know that 85% of your test participants complete the checkout process in under five minutes -- is that a good or bad thing? For this quantitative data to be of value, you would need to know comparative values and, for example, test other web pages or different variants of your product. And this effort is usually not effective:

If your goal is to understand human behavior to make design decisions, qualitative methods are much more effective in providing you with the information you need. -- Kim Goodwin in "Designing for the Digital Age"

For this reason, we also recommended at the beginning of this book not to lose time measuring usability. Our goal is to observe human behavior when interacting with our product, thereby identifying errors in our solution and understanding the cause of usability problems. Sometimes you need two, three or even more testers to actually identify the problem, but if after just one test participant you've watched you can say for sure what the cause (carpet wrinkle) of a problem is, then you can fix this problem immediately and check if it's actually been solved with another round of testing. And for such a procedure, a handful of test participants per round suffices.

Okay! But how many test participants are actually enough?

We were afraid that this answer wouldn't seem to be enough for you. Therefore, let's delve a little deeper into this, because the perfect number of test participants is a popular subject of discussion among usability experts. Steve Krug, the author of the usability best-seller Don't make me think!, recommends testing with three test participants per round.

His reasons include:

- Finding three test participants is less work than searching for more;

- Doing more than three tests on a single day means getting snacks for the people who moderate the tests and also for those who watch the tests;

- If you test with three test participants, you can do your tests and present the results on the same day.

Following Steve Krug's quote, many people plunge into a user test with three testers. If Steve Krug says it, what can go wrong? Honestly? Not much. Nevertheless, let's clarify a few things that are often overlooked when following Steve Krug's suggestion:

Steve Krug recommends three tests per round. Per round means that we test more than just once. He also refers to moderated and on-site user tests in his recommendation (more on that in the next chapter), so many of his arguments are based on the extra effort that further tests of this kind would cause. After all, in these moderated tests, somebody has to find the right test participants, plan the test dates jointly with them, and then conduct and moderate each single test. While we strongly recommend to do such moderated user tests ourselves, every single test participant causes a lot of extra effort with this setup. Since we describe in this book how user testing really works in practice and suggest unmoderated remote user tests, this argument doesn't apply in our case, because the search for new test participants is typically taken over by the user testing platform and the test participants moderate themselves. Finding further test participants doesn't necessarily mean much more effort with our approach.

In addition, Steve Krug started doing user tests more than 20 years ago. His book, where the proposal for three testers we mention comes from, is already more than ten years old and was published before the iPad was launched. There has been a tremendous amount of technology innovations in recent years and we now have to make sure that our digital products can be used on desktops as well as on smartphones, tablets, smartwatches and other devices. Thus, we have to deal with a lot of additional influences that affect the behavior of our users. After all, you use an online store on your smartphone (short sessions, often interrupted, rather than browsing) differently than on your desktop computer (longer sessions in a row, often with the goal of completing the purchase). Thus, only three test participants are not enough for our requirements.

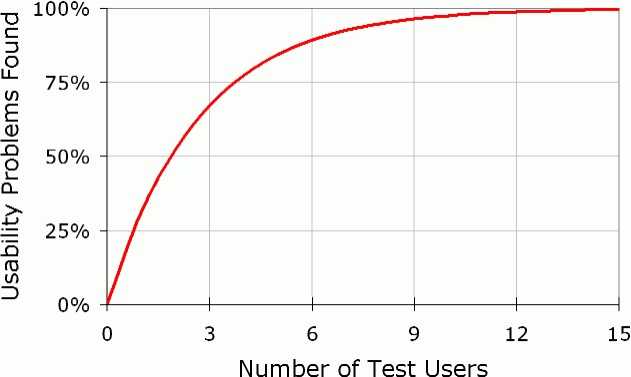

If we continue to search for the perfect number of test participants for user testing, we'll soon stumble upon a curve by Jacob Nielsen -- another well-known name in the context of usability.

In 2000, Jacob Nielsen published a statistic that has since been circulating in the specialized circles:

On the X-axis of this graph we see the number of test participants, while the usability problems are displayed as percent on the Y-axis. What's immediately striking is that the number of detected usability problems rises sharply up to the first three test participants. Thus, up to the third testing user, each test also shows many new usability problems. The number of new discovered problems decreases sharply after the fifth test of a round, and at the latest after the twelfth test you'll discover virtually no new usability problems. What we have here is the law of diminishing marginal returns. At some point, new input (new test participants) only provide very little additional output (new usability problems). The perfect cost/benefit ratio in user tests is thus somewhere between the third and sixth participants in a testing round. What Jacob Nielsen is showing us with this graph is that from an economic point of view, it makes more sense to test with a smaller number of participants (about three to six per round), fix the discovered problems immediately and then conduct further testing, rather than conducting individual test runs with a larger number of test participants.

While Krug and Nielsen suggest a different number of test participants, they agree on one thing: It's rather less about how many people in total you should test with but more about how user testing should be an ongoing activity. More important than finding the exact number of perfectly matched test participants, is to conduct your testing regularly. And in order to achieve this you need a pool of available test participants as big as possible. Let's have a look now at where you can find this.

Where to Find Your Test Participants

Because we don't have to limit ourselves to our target group, there are many opportunities to get test participants:

- Within the family, friends or acquaintances circle;

- In another department of your company;

- By placing an ad on a job portal;

- By posting an ad in schools, universities or colleges;

- By placing a classified ad in daily newspapers;

- On your Facebook page;

- On Twitter (#betatesters, #testmyapp);

- Via a survey on your own website;

- On portals like Hacker News, Reddit or Product Hunt;

- In existing pools of usability platforms

Another suggestion for quickly finding test participants is to approach people in coffee shops or shopping malls and try to persuade them to sacrifice some of their time to do a user test. The incentives to achieve this are either purchase vouchers or cash. This method is widely used in the U.S. and has hip names like "Guerrilla User Testing" or "GOOTB - Getting out of the Building". But a few things are often overlooked with the hype of these methods. "Getting out of the Building" is quite costly -- at least, if you want to do a few tests per week. Please don't misunderstand us. Leaving the office for user tests and doing quick tests in cafés is a great idea -- but in practice it is often not as easy to implement as it looks at a first glance. In addition, you need an effort to convince people in coffee shops to chat, because actually they are there because they want to be left in peace.

In this book, we are looking for a process for user testing that works in the long term, without hurdles and with little effort. The whole thing should also be independent of the availability of a single person, so that testing continues even if the person who normally performs the tests is currently unavailable. In addition, these moderated tests solve our problem of finding test participants only for a short time, because what should you do if you need a quick feedback on your new solution and you don't have time to moderate the tests? Ideally you need -- for tests that actually work in practice -- a pool of constantly available testers who are able to perform your tests without your intervention.

Here's the good news: There are already online services which have identified this precise problem and offer a solution. These services have pools of thousands of testers who are immediately available for user testing of a wide variety of products. The people in these pools have already been told what is expected from them in such tests, and the platforms constantly monitor the quality of their own testers. Thus, you not only avoid the search for testers, but also having to explain to them how they should perform. In addition, these people conduct the tests on their own devices and at a point in time they can choose themselves. The platform will also pay the testers and you'll get videos (usually within hours) of how the testers interact with your product while hearing what they think. You usually pay between 20 and 90 € per test on these platforms.

Your effort is therefore limited to the one-time setup of your test and the selection of the desired test participants.

As we can completely eliminate most of the hurdles to testing, such remote user tests are a good basis for tests which will really work in practice.

Conducting the Tests

After having created a test scenario with the most important tasks and now that you know where to find suitable test participants, it's time to show you how to run user tests by yourself. For this purpose, we'll simply assume that you haven't had any experience with user testing (or have forgotten everything again), so that we'll start at the very beginning.

As we've already mentioned in the first part of this book, there are two fundamentally different user testing methods:

- Formative User Testing

- Summative User Testing

Formative user testing is used throughout the development process to continually find problems in a product. On the other hand, summative user testing can be thought of as a kind of quality control, typically done at the end of the development process, in which the usability of a product is quantified and compared to that of other products.

In short: Formative testing is about improving a product, and summative testing is about measuring the quality of a product.

Based on this definition, it should be clear why we're only concerned with formative user testing in this book, because even if it can make sense to measure the quality of your product, this doesn't really help you to improve your product. This is what it's actually about: We want to show you how you and your team can continually improve your product with the help of user tests.

After introducing these two fundamentally different user testing methods (and briefly explaining why we prefer formative user testing), we still need to describe the two different ways in which user tests can be performed:

- Moderated

- Unmoderated

The difference is that in the case of moderated tests you have to be present (on site, via Skype, etc.) to guide the participants through the tests, whereas with unmoderated tests you don't need to be present, because the participants conduct their testing independently and, so to speak, moderate themselves.

There are pros and cons for both of them, so we'll briefly introduce you to both moderated and unmoderated user tests, before finally deciding what kind of user testing we would do if we were you at the end of this chapter.

Moderated User Tests

Moderated user tests could be described in one sentence like this: You ask somebody to use a product (a website, an app, a can opener, whatever) and think out aloud while you watch them and listen carefully to what's crossing their mind.

What's most important in these moderated user tests, according to our experience, is to avoid creating an uncomfortable exam situation, because if it happens, your test participants will be afraid of doing something wrong: They won't say everything that crosses their mind, so that you won't actually be able to understand their behavior anymore. However, since the mere mention of the word "test" is enough to remind people of their school days and make them nervous, we've become used to having to assure each participant right at the beginning of the test that it's impossible for them to do anything wrong, because it's not them we're testing, but the product.

But to say that we're testing the product and not our test participants is only the beginning. The next thing we need to do is clarify that our ultimate goal is to discover as many problems as possible, and certainly not to have the test participant pass the test. Without saying this, it may happen that people avoid giving negative feedback because they don't want to hurt your feelings. We solve this problem by addressing it directly and by encouraging our test participants to be as critical as possible, because this is the only way we can actually learn something.

After you tell your test participants that there's no way they can do anything wrong and to be as critical as possible, the actual tests can start. Just introduce the product to be tested and explain briefly what this product is intended for. Correct? No. In fact, you're doing exactly the opposite. Instead of explaining your product, you should ask your test participants to give you a quick explanation of what they think the product is for (as already discussed briefly in Chapter 4).

Thus, in the case of our practical example, Pawshake, we tell our test participants:

Please take a brief look at this page and say out aloud what you

think. Please don't click anything yet and answer the following

questions: What's the first thing you notice? What could this

website be about? Who is this page for? What products/services

are offered on this page?

The beautiful thing about this method is that it saves you having to explain your product at the beginning of the test. In fact, you should never do this because you're missing the chance to see if anybody outside your team actually understands your product. What is less beautiful about this method, however, is that you'll probably be shocked by how confusing your product is for most people, that is, if you haven't conducted any user tests yet. Apart from this, an excellent start for a user test is to ask your test participants to explain your product in their own words right from the beginning. Once they've done this, which usually takes no more than two to three minutes, you can present the previously created test scenario to them and start the actual user test.

Of course, it won't be always easy for you to watch people fail to understand your product, and you'll feel the urge to explain it to them. But we insist that you shouldn't do this; just watch what your test participants do and what exactly they think/say while doing it, because even though it hurts, the insights from these user tests are incredibly valuable when it comes to making your product simpler, clearer and easier to understand. The motto is therefore to just shut up and limit yourself to occasional nods and, as described in Chapter 4, make appreciative utterances such as "mmm", "ahh", or "okay". And if a test participant asks how this or that works, you shouldn't even try to explain your solution -- just ask how they imagine how this or that could work. In addition, you can point out that you can only answer questions after the test, because you want to find out how understandable or self-explanatory your product is.

So, as you can see, moderating these user tests is not that easy, and it will happen to you over and over again that you are "helping" your participants without actually noticing it by giving them instructions on how to use your product. This risk is particularly significant when testing your own products, without having internalized that the goal is to discover as many problems as possible and not to pass the tests. However, this isn't a problem that can't be overcome by always remembering that user testing is about discovering problems. It's easier, of course, to test other people's products, because your self-esteem in no way depends on passing the tests, but solely on finding as many problems as possible.

Another important part of these moderated user tests is documenting or recording the individual tests. Ideally, you should record each test on video to watch it again later, but of course, also to show the tests to your team. In the case of a digital product, you shoot the screen or use software to record the screen, and most importantly, record the voice of the test participants to capture their thoughts during the tests.

In our opinion, the best way to conduct moderated user tests is explained in chapters 7 and 8 of Steve Krug's book, Rocket Surgery Made Easy. Steve Krug explains the whole process and provides a number of useful checklists to make sure that you make all the necessary arrangements to successfully run moderated user tests. These checklists cover several pages, which should make it clear how much there really is to consider if you want to conduct a moderated user test. And since it would be pointless to try to describe the whole process better than Steve Krug (because his description is actually sensationally simple, clear, and understandable and it would be a plagiarism to repeat his process here), we simply advise you to read this absolutely worthwhile and extremely useful book.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Moderated User Tests

Advantages:

- You can ask questions during a test to better understand the test participant's behavior.

- You can improvise during a test and, for example, give a test participant an additional task that has only arisen from the test.

Disadvantages:

- Planning, organizing and executing individual tests is extremely time-consuming and inflexible, as you have to be present during each test to moderate it.

- Documenting test results (preferably in the form of video including audio recordings) requires preparation and technical equipment.

- Moderation errors will distort your test results (A classic one: false, positive test results because you disclosed the correct use of your product to your test participants without noticing it).

Unmoderated User Tests

Unmoderated user tests could be described in one sentence like this: You ask somebody to use a product (a website, an app, a can opener, whatever) and think out aloud while you watch them and listen carefully to what is crossing their mind.

If you're an attentive reader, you'll probably have noticed that this description of unmoderated user tests is exactly the same as the one we provided previously for moderated user tests. That's because both moderated and unmoderated user tests are basically the same thing. The only difference lies in the way these user tests are carried out, because while in moderated user tests it's essential that somebody who leads the participants through the tests is present during testing, in the case of unmoderated tests the participants themselves take over this task.

It only became possible to do unmoderated user testing when the first remote user testing platforms came onto the market about ten years ago. On the one hand, these platforms provide participants to product teams for their user tests (as mentioned in the previous chapter), and on the other hand, software solutions with which these participants can carry out their own tests and record them. The entire process, including payment to the test participants, is taken over by the platform, with the advantage that product teams don't have to invest time in the recruitment of test participants, nor do they have to worry about organizing and conducting individual tests.

Thus, instead of looking for test participants, planning and organizing tests, and moderating every single test themselves, product teams have the opportunity to have this done by one of these platforms. In the case of our practical example, Pawshake, we simply used Userbrain -- our own remote user testing platform. All we had to do was enter the URL of the website and the previously written test scenario in Userbrain and choose how many test participants we would like to test with. Done! A few hours later, we received the test videos (screen recordings including audio comments) and were able to evaluate the individual tests (see the next chapter).

Advantages and Disadvantages of Unmoderated User Tests

Advantages:

- Test participants "moderate" themselves.

- Test participants can test anytime, anywhere, on their own devices and in an environment familiar to them.

- You save time because you don't have to plan and organize the individual tests.

- You enjoy flexibility and don't have to be present while the tests are being conducted; you simply watch the test videos when you have the time to do it.

Disadvantages:

- There is no way for you to intervene during the test if something goes wrong.

- You can't ask questions during a test to better understand a test participant's behavior.

Our Recommendation

In our opinion, user testing is all about one thing, i.e. actually doing it, preferably, of course, on a regular basis. Thus, it doesn't really matter whether you decide to conduct moderated or unmoderated tests; as long as you do test, you're doing everything right, so to speak.

The less experience you have with user testing, the sooner we advise you to conduct unmoderated tests. As mentioned earlier, this not only means much less preparation and effort in the implementation, but also that your test participants moderate themselves. And this isn't only something practical, it also has the added benefit of not inadvertently telling test participants how to use your product during testing, and thus avoiding false positive results.

Another important point is the experience of the test participants that you can find on the previously mentioned platforms for unmoderated user tests. Most of these people have already participated in a variety of user tests, and while many product teams believe it would be better to test with inexperienced participants, our experience is that the more often a person has already participated in a user test, the more valuable and useful this feedback will usually be for you and your team. There is a simple reason for this: experienced test participants know exactly what is expected of them, i.e. to read the test scenario carefully, complete all tasks and think out aloud all the time along the way. And this thinking aloud is difficult for beginners, so that their testing is often less useful, because without understanding exactly what is going on in their minds, it's usually impossible to understand their behavior.

Finally, we have to make it clear that we are huge fans of moderated user tests and urge everyone to moderate their own tests. The reason for suggesting unmoderated tests to you is best summarized in the following sentence, with which we end this chapter: Unmoderated user tests are so simple and efficient that you will really be able to do them in practice.

Assessing the Tests

In the previous chapter, we described how to conduct your own user tests and explained that these are best documented in the form of videos. In this chapter, we will show you how to assess these test videos and what you should pay attention to.

Before we show you exactly what's important in this step using a Pawshake test video, the two most important goals we follow when assessing user tests are these:

- We want to discover as many problems as possible;

- We want to understand why these problems occur.

The first point is one we've already mentioned often enough in the course of this book, so it shouldn't come as a surprise anymore. But this is a good opportunity to repeat it again, because assessing a user test is in fact nothing else than embarking in the search of problems. That is, we are of course happy when something works, but we are even happier when something goes wrong.

This may sound a bit strange at first, but if you remember that our big goal is to improve our product with the help of user testing, then it quickly becomes clear that we'll only succeed in this if we do discover problems. If we don't find any problems, e.g. due to unskilful moderation or because we don't look closely enough at the assessment, then we can pat ourselves on the back because we've passed the user test, but actually, we've learned nothing -- at least nothing that will help us to improve our product.

But discovering a problem is really only the start, because the next thing is to understand what the reason for this problem really is.

What we're trying to explain here is that your observations aren't so much about capturing things in detail (who has experienced what problem, when, where, and how exactly), but rather about understanding why this problem was encountered at all. Why? Well, if we understand the reason why a problem occurs, we are in a good position to solve this problem and avoid it in the future.

And to understand exactly how this works, we're going to use a user test of Pawshake as an example, including some screenshots and our observations:

Pawshake's User Test Example

In this analysis, we'll skip the starting questions and go directly to the first task.

TASK 1:

Imagine that you're going to a concert in your neighboring town

next Saturday and that you won't be back home until Sunday evening.

Thus, you're looking for somebody to take care of your dog during

this time. This is something usually done by a friend, but this

weekend she has no time. However, she has told you about Pawshake

and said that you would find somebody there to take care of your dog.

Try to find a few candidates on this website to whom you would

entrust your dog during this time and compare them to each other.

Subsequently, choose your favorite and briefly explain your decision.

Link to the full video: https://bit.ly/2LlTEvW

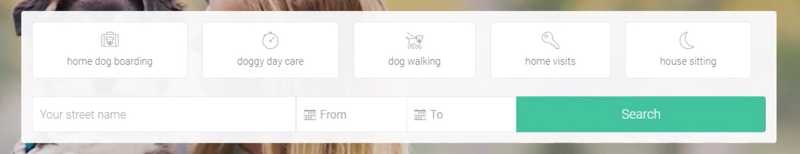

What stands out immediately here? The website is beautifully designed, without too much information delivered at once. And when you land on the page, you are confronted immediately with a search, which [...] probably leads to the main service of this site, i.e. the selection of dog sitters. Your street name...

The test participant enters his address...

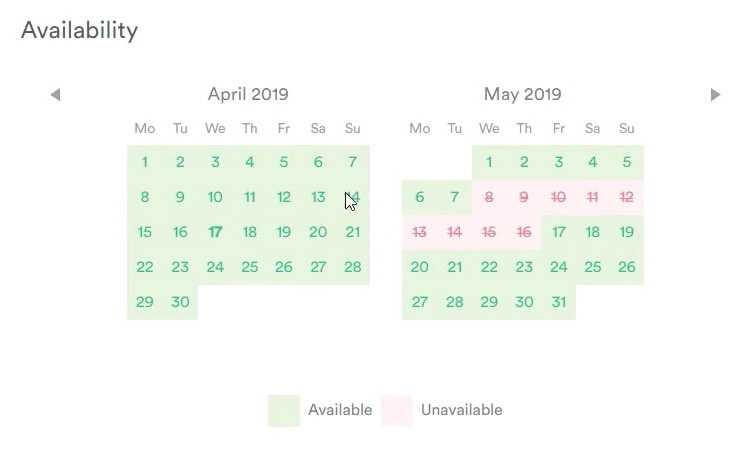

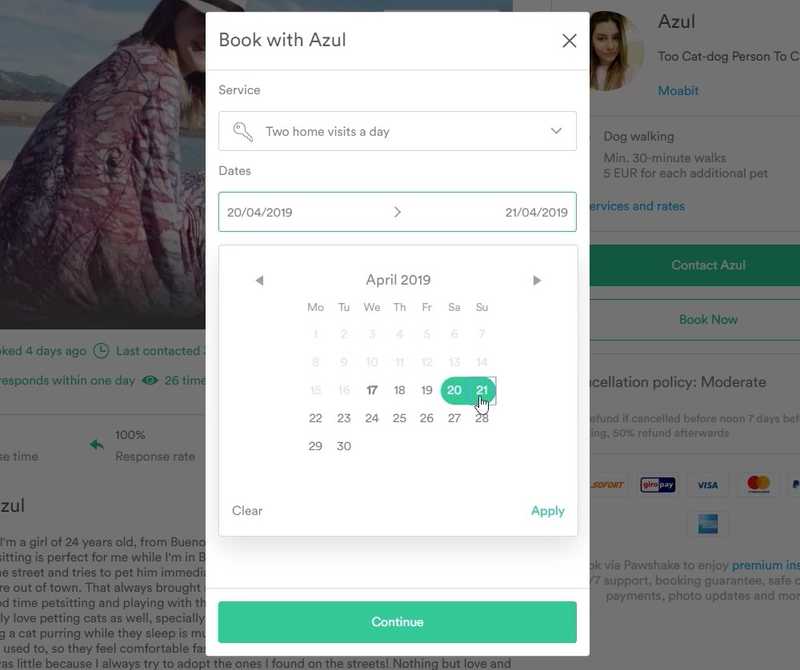

We want to have this next Saturday, that is, Saturday April 20, that's it. It's on this weekend that [your friend] has no time. You'll only return on Sunday evening. Okay, this means that I need something until Monday, that's what I'd have to book:

The test participant selects the period...

I don't know if the dates are inclusive, that's the first question that comes up here now. Does this mean Saturday morning to Monday evening or Saturday morning until Sunday evening? In my opinion, this isn't very clear, but I think it'll be Monday morning. I'll leave Monday for safety's sake for now and just click on "Search".

Our test participant selects Monday for safety reasons, which is understandable if you follow his train of thought.

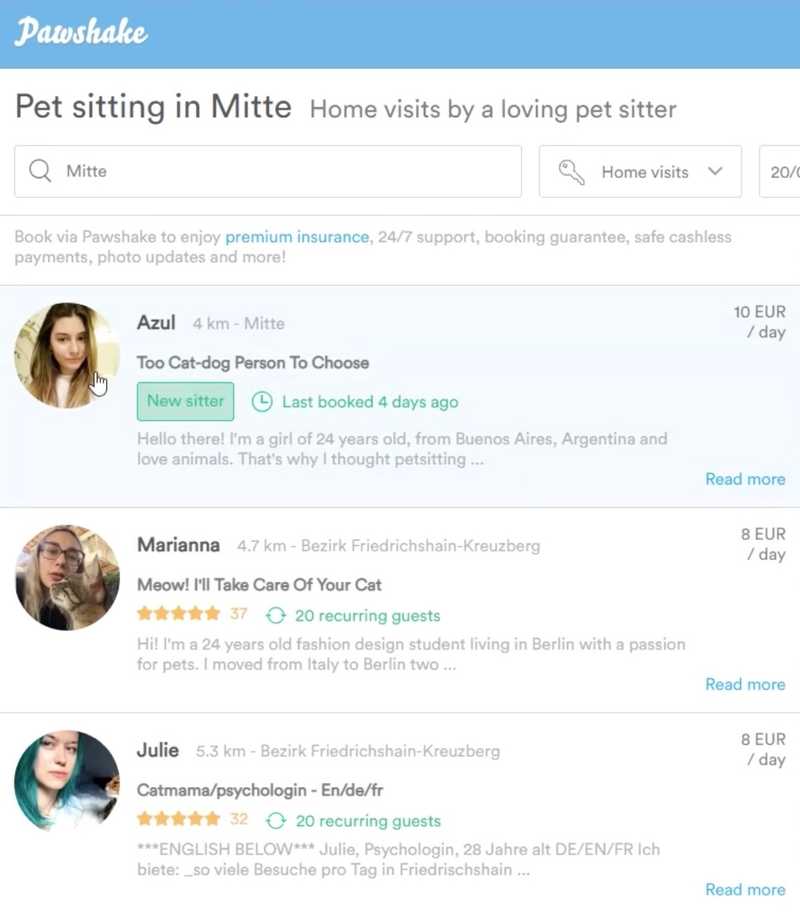

Incidentally, after our test participant didn't find a pet sitter in his vicinity, he looked for pet sitters in "Berlin-Mitte" to go on with his test.

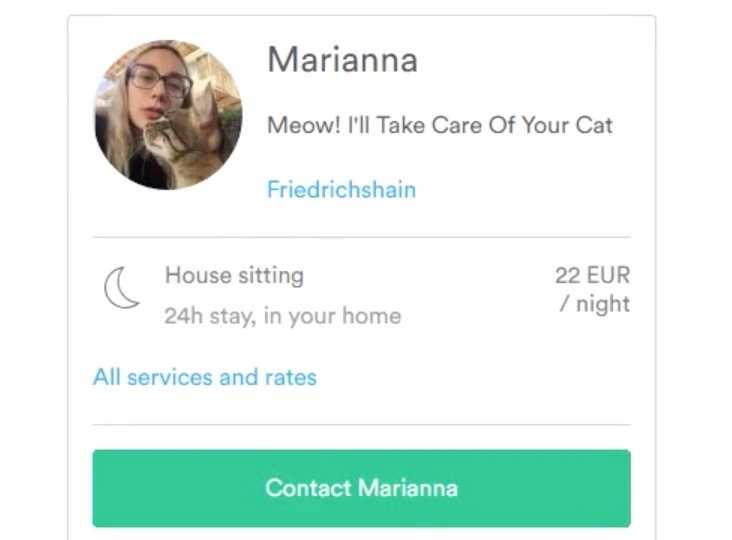

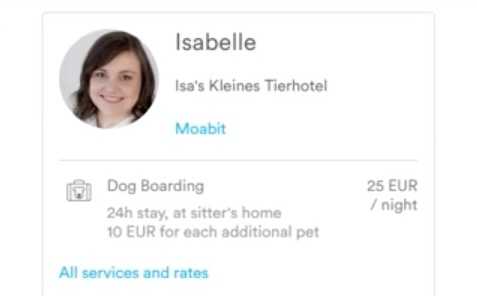

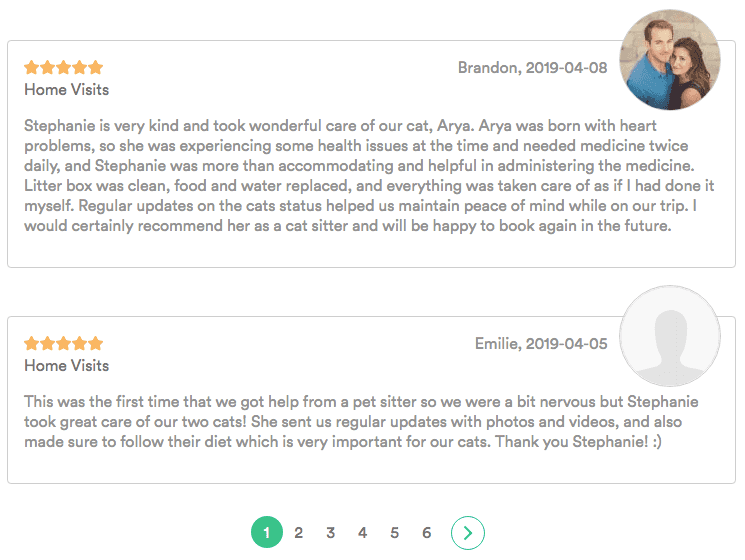

Ah, ok, perfect, now we've already quite a lot of different offers around Berlin [...] so I should take a look at a couple of them. For example, what about ... yes, here, Marianna looks good. Five-star rating, 37 reviews too and already 20 clients who keep coming back to book her. So, let's have a look. 22 € per night. Okay, that's of course rather expensive compared to the others

... hmmm, but here's 8 € per day [on the overview page] ... well, well.

Our test participant is somewhat irritated by the fact that a different price (8 € per day) is displayed on the overview page than in the right-side column on the detail page (22 € per night). At a second glance, he realizes that Marianna offers different services and therefore has different prices.

Nevertheless, the question arises as to why the same price or service is not emphasized on both pages in order to avoid this confusion.

Ah yes, down here it's again: "House Sitting" and "Home Visits". Ah ... okay, now I understand this. Probably what happens is that if I want Marianna to stay at my house the entire weekend, then I'd have to pay this rate, so for two nights or two days. And if I just want her to feed my dog every now and then, that's 8 € a day. Well then, compared to the others she's even quite cheap. I mean, 20 € down here with Peggy even [on the overview page]. Then 8 € is really cheap. Ah, but "I take care of your cat"; that's something I'm only reading just now. She has a picture of a dog, but only accepts cats. Is that correct? "Cats and dogs and" okay, "I would like to offer mainly a home visit service for cats and smaller animals". So this isn't a service offered for dogs, let's discard her.

Our test participant has just noticed that not all pet sitters on Pawshake seem to accept dogs. This was not necessarily something to be expected...

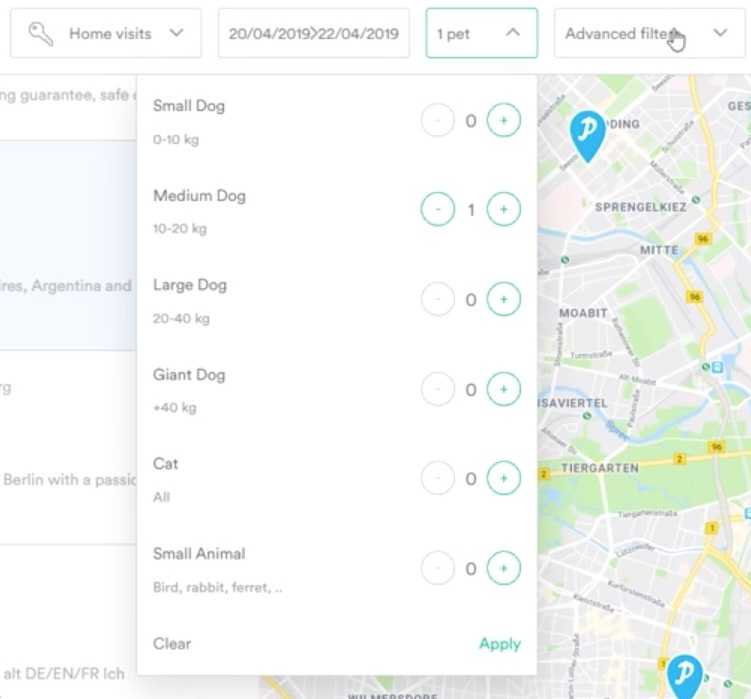

So, we'll take Julie then. What does it look like here? It doesn't say if she wants to take dogs or cats. And 8 € per day is even a bit cheaper, with 20 € per night. "As your cat(s) needs" ... again only cats, okay, yes, a pity. Can I somehow filter so that there are only dogs?

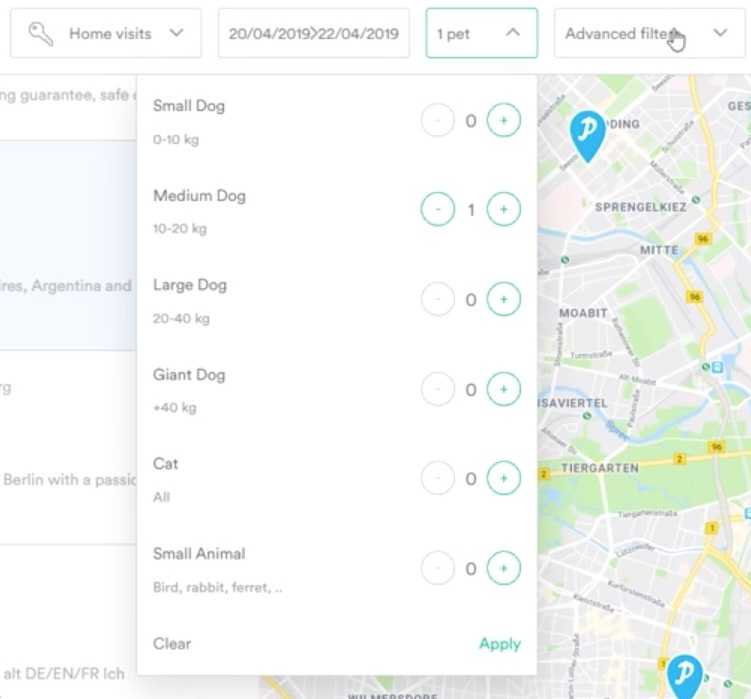

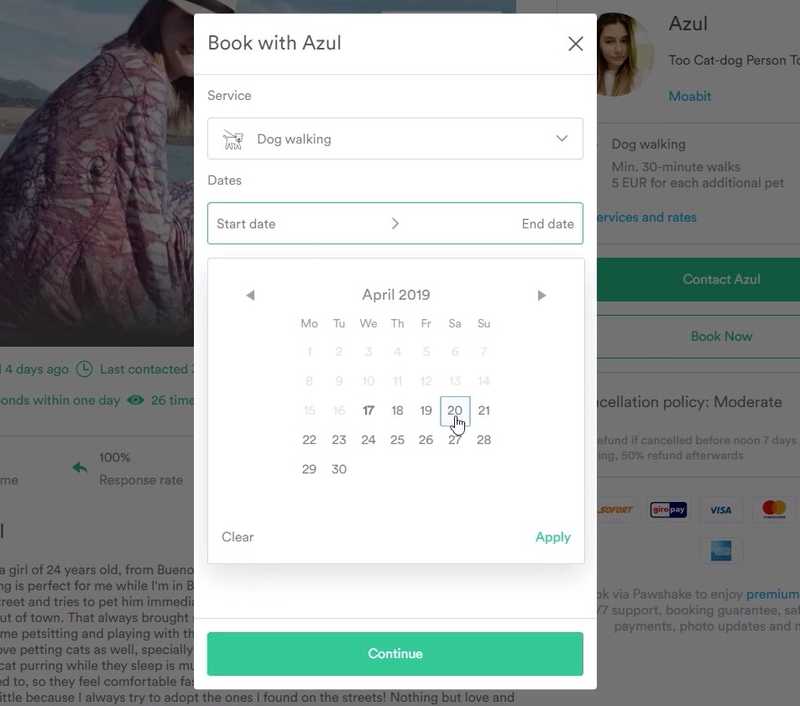

Yes, okay, I can. Let's say I have a medium-sized dog. Has that changed anything now? How do I search again? Do I search like this? [Clicks in the search field and confirms with Enter] Yes, okay. Well, and now it should really be limited to showing only people taking dogs. Oh no, Marianna is still here.

After our test participant realizes that there are seemingly several pet sitters who are not taking dogs, he is looking for a filter to display only pet sitters who also accept dogs. In fact, he finds the filter very fast and enters that he has a medium-sized dog. However, what our test participant overlooks (and we also overlooked it while testing the page) is that he would have had to click on "Apply" in the bottom right-hand corner of the filter to actually apply the filter. Instead, he clicks somewhere else, so that the filter closes again, and he wonders if something has changed or not... Then he just clicks the search box again, confirms with Enter and the search results are reloaded. Interestingly, after reloading, the filter still remains at "1 pet", giving the impression that the filter is now being applied. However, as Marianna is still being displayed, our test participant quickly realizes that it is possible that the filter hasn't worked, but doesn't give up and continues looking for a suitable dog sitter.

Yes, okay, how about Isabelle? She has a 5-star rating with many reviews and many clients. Apparently, she also has two cats ... oh, that's interesting, that you can create your profile so easily here and so personally. There, have a look ... Humboldt University, History. That's very nice. She has two cats. But we've already read this before. Well, "Unfortunately we cannot accommodate free-ranging cats, nor dogs." Okay, so, once again, somebody who doesn't want to take dogs, right? I mean, I see "Dog Boarding" here. Hmmm ... I thought she doesn't want dogs. Okay, here it says inside, she doesn't want dogs, so she doesn't want dogs. Let's discard her.

At latest by now the whole thing is a bit confusing, because Isabelle offers on the one hand "Dog Boarding" and on the other hand writes that she can't take dogs. Nevertheless, our test participant is not discouraged and continues his search...

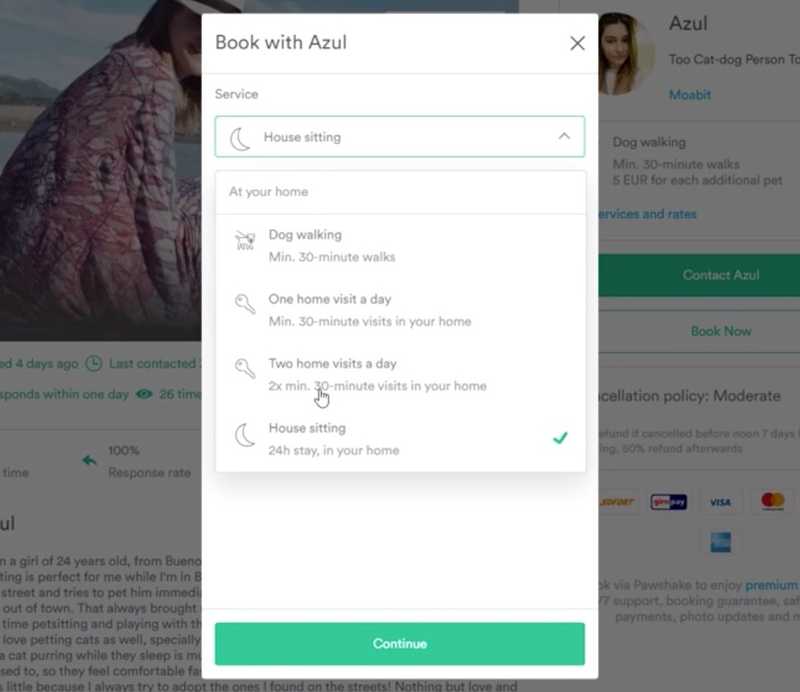

Azul, "[the] cat-dog person to choose". Perfect! She's new here, but that doesn't necessarily mean that she has to be bad. And she offers Walks. Okay, let's see. "I'm the kind of person that sees a dog walking [in the street and tries to pet him]", okay, so she likes dogs. Okay, she also offers "House Sitting". Wonderful! "Watch your pet overnight in your home" ... for 25 € the night. She also offers "Home Visits" and "Dog Walking" too. That seems pretty good. And she's also available in the period 20 to 22. That's nice. Yes, she's not been around for so long, but that doesn't matter.

After our test participant has found a suitable candidate, he tries, as required in the test scenario, to find other potential dog sitters to compare them to each other.

So, how are things with Aly from [...] Aly also has a 5-star rating with quite a few ratings. Let's see ... she also offers "Dog Walking", okay, much more expensive than Azul. She also offers "Home Visits", okay. What's the price comparison to the "Home Visits" here [to Azul]? Okay, Azul is cheaper too. Let's see, do I have to do "Home Visits"? [Reads in the scenario] ... "to whom you would entrust your dog at this time", okay.

So, I don't believe "Home Visits", but instead real "House Sitting". And since Aly doesn't offer this, she is unfortunately discarded.

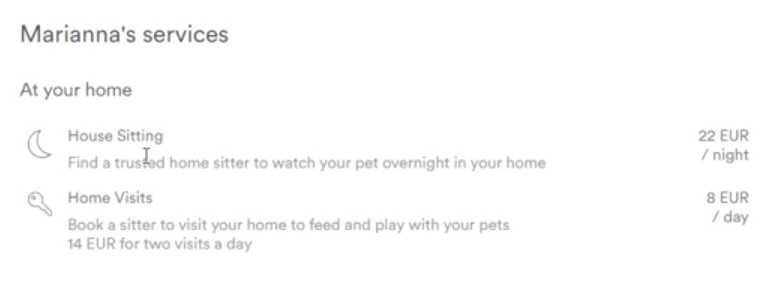

What is most interesting in the previous paragraph is that for the first time, our test participant is dealing with the kind of service he actually needs. As he correctly realizes, "Home Visits" are not enough, as he is looking for somebody to whom he can entrust his dog over time, and not just somebody who comes by to feed his dog. In this case, "House Sitting" would be the better choice, but if our test participant had already noticed the different services offered on the homepage, he would have been able to determine that the right choice would actually have been "Home Dog Boarding", since he is not necessarily looking for somebody who looks after his dog at his own home, but for somebody who takes his dog home with them and takes care of it there.

In this case, the vague formulation in our scenario is certainly a problem and something that we would correct for future tests (see Further Testing). Apart from this, there's a common problem here that we've also seen when watching other test participants: the differentiation of the services offered on Pawshake's homepage:

As you can see on the screenshot, there are five different services:

- Home Dog Boarding

- Doggy Day Care

- Dog Walking

- Home Visits

- House Sitting

Although the terms are well-chosen and you can establish with a bit of imagination what the differences between the services might be (as evidenced by some of our test participants), this presentation on the homepage has led to three problems (one of them also affecting this test participant):

- Test participants expected to receive more information when selecting one of the services (in fact, the selected service is merely outlined in green, the rest of the page doesn't change)

- Test participants were partly confused by the terms (for example, one of them thought that on Pawshake he would also find people to just take care of his house while he was on vacation)

- When test participants started their search without selecting one of the services (as in the case of the test participant shown here), then "Home Visits" was selected by default and applied as a filter on the overview page

And it is precisely this third problem which becomes fatal to our test participant, because he doesn't notice anything of this and therefore has to click through a variety of candidates to find those who also offer "House Sitting", when some of these candidates -- as unintentionally set by filter -- only offer "Home Visits". In addition, this test participant found that the filter for medium-sized dogs didn't work, which apparently meant that he didn't pay too much attention to the entire filter bar and instead simply resigned himself believing that the filters on Pawshake don't work.

But let's get on with the test:

So, what about Ula? Oh, okay. No, she also offers only "Home Visits" ... not "House Sitting", it's a pity.

What follows is a classic example of a comment that you'd love to hear about your own website, but should not mislead you:

Well, really, dealing with this page is very easy. You simply click around these different profiles, in which the users themselves can indicate their rates and offers, their experience and qualities. It's all very intuitive and easy to use. In addition, the entire interface is consistent and not crowded with information. That's all very, very easy.

Of course, this sounds great, but the wrong conclusion to draw from this comment is that the page is already so intuitive and easy to use that you don't even need to test it anymore. In fact, this comment is rather a friendly phrase that you hear over and over again in the course of user testing, because most people are reluctant to give negative feedback and even if they have obvious problems, they'll say that everything was very easy. It should probably be taken with a pinch of salt...

What about Stephanie ... maybe she offers this. Ah, okay, "House Sitting" ... much more expensive than Azul, but still. Let's see, does she even want to take dogs? "Husband and our two cats" ... okay ... "my services, I can visit your home twice a day to play, feed and groom your pet". Yes, she says "your pet", so probably dogs are also included there. Ah, you can even read reviews here, that's nice.

Perfect, "Cat Sitting" ... let's see, maybe she has also sat for a dog. "Catlover ... excellent care of cat, cat sitter ... cat sitter", hmm ... oh, is this maybe about a dog? [...] I think she also takes dogs. At least she offers "Dog Walking", so I assume that dogs are included in "House Sitting".

The problems previously described in connection with the setting of the filter are still going on. Meanwhile, our test participant is already reading client reviews, hoping to find out if a pet sitter is taking dogs or not. Had the setting of the filter previously worked, only pet sitters who also take medium-sized dogs would be displayed. Regardless of this, the question arises as to whether it might make sense to show an overview of all the animals taken care of on the details page of a pet sitter...

Okay, then I'll try again to find another person who meets my criteria. Here, Shani, she looks nice too. Again cats ... ah okay, she also grew up with three big dogs. Let's see ... "Doggy Day Care", okay. So, you can leave the dog for the day over there. She also offers "House Sitting", but for the highest price so far. Okay, then we'd have three to choose from, I think.

And now back to the filter:

One thing I noticed is that even though I said I really only want to have "Medium Dogs" [...], I still get somebody like Marianna, who says she only wants to take cats.

The filter still seems to be set even now, though it's actually not used, because you would have to click on "Apply" first. But all right, let's get back to a problem that we've already noticed earlier:

Okay, so in the end I'm gone for one night and one day. This means that if I book the service, I'd say I need "House Sitting" for one night ... or does that actually have to be for my dog? [He reads again in the scenario] Does he need "House Sitting"? Yes, [...] let's say we need one night of "House Sitting" and then, for the next day, either something like "Doggy Day Care" or something like "Home Visits". Okay, thus, "30 € for two visits a day". Okay, so Shani stands out, she's very expensive. I would pay 70 € total for the day and the night I'm away. Maybe I should even have to book two days ... it's just a bit too unclear to me how this is divided ... and where the line between "House Sitting" and "Home Visits" is. Yes, I'm unsure about this. But in any case, Shani is definitely a little expensive, so I would discard her.

On the one hand, we're having to deal once again with the problem that the formulation of our scenario is not specific enough -- something which we would definitely improve in a second testing round. Apart from that, it is also noticeable that our test participant doesn't really know which service he should actually choose or how he should combine different services. Watching several test videos, we noticed that during testing, different participants develop different so-called "mental models" of how the individual services work. For example, this test participant believes that he would have to book a total of three services: two "Home Visits" for daytime (Saturday and Sunday) and one "House Sitting" for the night from Saturday to Sunday. To be honest, we ourselves don't really know if that would be right or whether it would even be simply enough to book "House Sitting"...

Well, it's either between Azul, who's new here, or Stephanie, who's been around for a while. Both offer "House Sitting" and "Home Visits". However, one of them for 25 € and for 10 € and the other for 35 € and 15 €. This means, assuming I'd have to book the day for Saturday, then the night for Saturday, and the day for Sunday, then I would reach 45 € here and 65 € there. A price difference of 20 € is striking. And that's why I would end up by choosing Azul.

Apart from the fact that we aren't sure if it's really necessary to book three services, the test participant doesn't go to too much trouble to compare the two pet sitters. By the way, Pawshake has solved this by simply opening every pet sitter on a new tab.

I think that this website does a very good job of introducing people and creating a sense of trust between the dog-sitter and the consumer. What's the second part of the task?

TASK 2:

Now you want the person you've decided should take care of your

dog, to do it next weekend. You can consider this task as completed

before entering payment details.

So, we'll probably need "Two home visits a day". Start Date is April 20 and End Date ... that's the question now. Is the end date Sunday? Can I ... (The test participant tries to enter April 20 as start and end date) ... ah, okay, I can do this (start and end date on April 20 worked), then it's clear that the end date will be Sunday. If I can say that it'll be from 20 to 20, then what I want is this (from April 20 to April 21).

As already happened on the start page, our test participant is still not sure whether he has to book something for Monday or not. However, when he realizes that he can set start and end date to the same day, he realizes that Sunday is the correct end date. In fact, this is a very nice example of how the functionality of an interface element can show you how a product works.

And here's a great example of how a constraint in the interface can help you to understand a product:

So, "Service: Two home visits a day"... would I also need "House Sitting"? Well, I think "Two home visits a day" would fit [...] I'm a bit uncertain about the difference between "Two home visits a day" and "House Sitting" is. I don't need her to be at my house 24 hours a day. I think "Two home visits a day" should be enough.

Our test participant has been confused for some time now about which service to choose, but since he can only choose one service at a time, at least he now knows that he can't combine "House Sitting" with "Home Visits". At this point it would obviously be a good idea to revise our test scenario for the next round of testing and make it clear whether we're looking for somebody who comes in on Saturday and Sunday to feed the dog ("Home Visits"), somebody who stays at our home from Saturday to Sunday to look after the dog ("House Sitting") or somebody who can keep the dog at their own home from Saturday to Sunday ("Home Dog Boarding"). As soon as we describe this more clearly in the test scenario, we'll be able to find out in a further round of testing how well the differences between the individual services are actually understood.

But let's continue with this test. So, what happens if our test participant clicks on "Continue" in the previous overlay?

So, if I click on "Continue" ... hmmm ... okay, so, hasn't it worked as it should now or is this just the next step?

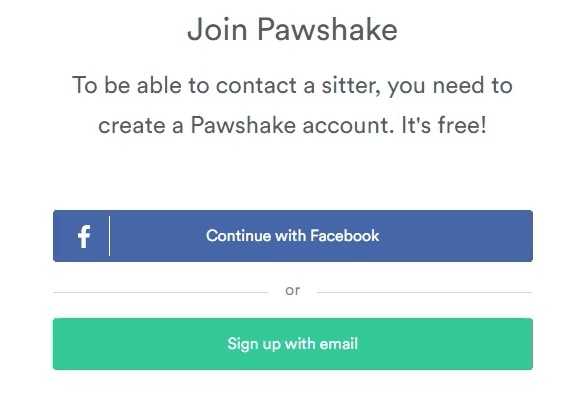

Our test participant seems to be a bit confused or even believes that an error has happened (see screenshot).

On this page it would probably be best not to talk generally about joining Pawshake but, for example, repeat the name of the pet sitter you're about to book. "Join Pawshake to book Azul" might already be a great help to avoid this confusion. In this case, our test participant assumes that an error has occurred and therefore navigates back a step to get to the previous overlay:

Apply, continue ... oh no, I've done "Dog Walking" now! Oops, sorry. 20 to Sunday ... and we want "Two home visits a day". That should be right! And then we click on "Continue" ... and apparently I have to create an account.

After our test participant went back and opened the overlay again, the service was automatically reset to "Dog Walking", something which our very friendly test participant even apologizes for (although this is, of course, a site usability issue). He also had to re-enter the date, which was now required for the third time (first on the homepage, then for the first attempt to book Azul and now when booking again). In fact, we were able to observe in each individual test this problem of the date chosen on the start page or the filters not being saved or taken over, something which annoyed some people quite a bit more than this participant.

By the way, after this, our test participant creates an account and looks at the order confirmation page a bit more closely. However, we finish the analysis at this point and believe that with this example, you (hopefully) have a good understanding by now of what to look for when assessing user tests.

In the next chapter, we'll take a look at how you can document these test results or share them with your team.

Sharing of the Test Results

In this chapter we briefly describe the best way you can share your test results with your team. For this purpose, we'll explore three different ideas that are not only much more efficient than creating usability reports, but also much more fun.

Idea 1: The Three Biggest Problems

As mentioned in the previous chapter, the goal of assessing user tests is to discover as many problems as possible. Theoretically, of course, you should capture, analyze and pass on all these problems to your team, but in practice it won't work. Let's explain briefly why...

Apart from the fact that it would be extremely costly to accurately detect and analyze all discovered problems, none of your team will normally read this analysis. The reason is quite simple: product teams usually have more important things to do than look at user testing results. Of course, you can find that this is a good or a bad thing, but in any case, you should recognize it as a reality if you want user testing to really work in practice.

In addition, nobody really wants to read a document describing their own shortcomings in detail. Because this is precisely what a usability report is in the eyes of those who developed the product being tested. Even if you now know that discovering problems is extremely desirable (because it shows you how to improve your product), for the rest of your team they're still nothing more than problems or mistakes which should be basically avoided. Accordingly, they'll feel criticized if you submit all of these problems at the same time to them.

So, even if it's well-intentioned, just save yourself the work and focus instead on the three biggest problems you've discovered in the user tests. Of course you can also handle the remaining problems at some time, but we suggest that you keep them away from the team, and instead focus solely on persuading your squad to take care of these big problems and not get distracted from other things. You'll also see that you should do more rounds of user testing anyway, once these problems have been solved. You'll learn why in the next chapter.

But first of all, the three biggest problems from our user test example, which we would pass on in a similar way if we were part of Pawshake's team:

The dates entered are not saved

If the test participants select a period on the start page, it isn't added as a filter on the overview page. This led to test participants being offered pet sitters who weren't available during the requested time frame. In addition, participants had to re-select the period after they found an available pet sitter and wanted to book them.

The "Apply" button for the filters is overlooked

Part of the test participants overlooked the "Apply" button for filters. Since even if the "Apply" button isn't clicked, these filters look as if they have been selected, and results which obviously don't match the filter criterion are displayed at the same time, the impression is that the filters don't work. This means that test participants who have been looking for a dog sitter were repeatedly offered pet sitters who wanted to take care of cats only.

The different services on the start page are unclear

Some test participants expected additional information about the service when selecting it from the search mask on the start page. In general, the different services (Home Visits, House Sitting) caused confusion. We'll soon be doing another round of testing with a customized test scenario to see exactly how significant this problem really is.

While we could observe other problems in our user tests, such as using the datepicker or the confusion on the sign-in page described in the previous chapter, we should spare our team this information and instead simply explain the three biggest problems in more detail and maybe prepare highlighting videos to watch together with our team. And this leads us to the next idea...

Idea 2: Watch Test Videos Together

Usability expert Jared Spool published a remarkable article in 2011 entitled "Fast Path to a Great UX - Increased Exposure Hours". In this article he describes the research results of UIE, the world's largest usability research organization of its kind, when trying to answer the question of what teams can do to create great user experiences. The answer is: "Exposure Hours", or in other words, the number of hours each team member spends watching people interacting directly with their own or a competitor's product.

In his article, Jared Spool writes that each team member must be directly exposed to the actual users. Teams with a dedicated user research expert who watches users and then presents the results in the form of documents and videos don't offer the same benefits. Being directly exposed to the actual users makes the crucial difference that actually leads to improvements. Incidentally, the best results would be provided by teams who do their research on an ongoing basis and whose members spend at least two hours every six weeks watching people use their product. And the more regularly teams do this, the better their results would be.

As different methods of exposing themselves to their users, the article mentions field studies in which teams visit their users in their natural environment and observe how they actually use their product, as well as usability and user testing, both moderated and unmoderated. It also describes how painful it is to watch somebody having trouble using your product and how much more painful it is to have to watch the next person a few weeks later still having the same problem.

We can actually confirm this from our experience, because we feel the same way when we look at the user tests of our own products or solutions together. One thing is for sure above anything else, and it's probably why watching user tests together is so effective: The more often you and your team observe the same problems, the more frustrated you become and the more important it becomes for you to resolve those problems -- and the happier you'll all be once you've solved those problems.

Idea 3: User Observation Lunch

With us, the viewing together of test videos usually takes place at irregular intervals. In one week, for example, we spend a whole morning just looking at test videos, but in the next week we don't really have the time to do it again. It's obvious that making a habit out of this is not the ideal thing.

The solution to this problem was provided by a Userbrain customer: the User Observation Lunch. The idea behind this is extremely simple. Once a week, your entire team meets for lunch to watch one or more user test videos together. Ideally, you'll first want to watch the videos in advance yourself and make a note of the biggest problems, so that you or your team colleagues don't have to take notes during the meal. At least that's what John, our Userbrain customer who brought us this idea, does, meeting with his team once a week for a "User Observation Lunch" to watch their weekly Userbrain test video together.

The nice thing about this idea is not just that your entire team comes together, which in itself is already positive, but a point that Jared Spool describes in his article mentioned above: the fact that you'll see the best results when not only your designers and programmers watch the user tests, but also all other stakeholders, such as product managers, executives, support staff, and quality managers. When everybody really comes together to watch user tests of their product, decisions suddenly are no longer based on the opinions of individual team members, but actually depend on what your users really need, and this not only leads to a great user experience, but to a simple, clear and understandable product and thus, happier customers.

Further Testing

Okay, so you should now know how to conduct your own user tests and share your test results with your team. All that remains is to remind you briefly how important it is to continue testing and not stop immediately after just one test round.

The most obvious reason for further testing is that once your team makes a change to your product to solve one of the problems you've discovered, you can't possibly know if this change will actually solve the problem. Besides, you wouldn't be the first to create a completely new (and absolutely unexpected) problem by solving the first problem. That's why it's necessary to re-test your product after each change.

As briefly described earlier, another reason is to re-test the test scenario used to get better test results. For example, in the case of Pawshake, we'd describe in more detail what kind of service we wish for our dog so as to better test whether our test participants really understand the difference between the individual services.

Old: Try to find a few candidates on this website to whom you

would entrust your dog during this time and compare them to each

other.

New: Try to find a few candidates on this website to whom you

would entrust your dog to take it home with them during this time

and compare them to each other.

Apart from this, we could include details in our test scenario to make it even more realistic:

Although your dog has no problem with cats, it is very shy in

front of other dogs and you're looking for a dog sitter who does

not have a dog of their own.

Incidentally, this idea comes from a user test with a dog owner who, during her test, said she was looking for a sitter without a dog because her own dog is afraid of other dogs. This small detail is a good example of how a specific test scenario can help you to not necessarily have to test people from the target group to get realistic test results.

Another reason to continue testing is that most products today aren't used exclusively on a single kind of device. Especially in the case of websites, it's quite normal for them to be accessed by different people on different devices and should therefore be tested on all these devices. In other words, if Steve Krug and Jakob Nielsen talked about three to five test participants per test round, of course this also applies to different types of devices (desktop/laptop, tablet, smartphone), since the use on a desktop computer often looks or works completely different than on a smartphone (as already described earlier).

Apart from that, there is one more reason to test, namely the fact that you can almost never test all the functions of a product in a single test round. For example, in the case of Pawshake, we tested only three of the tasks mentioned earlier. Next, for example, it would be interesting to test how to send a message to a pet sitter or rate him/her. And we are not even talking about testing the other perspective -- that of the pet sitter...

As you can see, there are still some things to be tested and good reasons to do so. That's exactly why we developed the previously mentioned remote user testing service Userbrain: at some point we noticed that although we talk all the time about the importance of regularly conducting user tests, we've been testing too little ourselves.

In addition, in the third part of this book we offer you a collection of test scenarios, so that you don't run out of ideas for further user testing, because as described earlier, the more regularly teams observe how people interact with their products, the better the results these teams will deliver.