How to Write Effective Tasks for Usability Testing

Published December 4, 2025 by Markus Pirker in User Testing

Tasks that are not well-crafted can result in ambiguous outcomes, thus complicating the how you analyze and identify usability problems. This article is designed to assist you in creating effective usability test tasks that yield valuable feedback from your testers.

Understanding User Interactions

Before creating your test, it's important to understand how real world people interact with your product.

Consider these questions:

- Which main actions need to be performed by users?

- What are the key goals of your business?

- What insights do you want to learn from usability testing?

Answering these questions will help guide you to pinpoint essential user actions and design your tests tasks.

Creating Clear and Concise Tasks

When crafting your usability testing tasks, follow these best practices:

- Use one-sentence tasks: Keep each task simple and to the point.

- Ensure tasks align with user goals: Focus on real user actions, such as signing up, searching for information, or completing a purchase.

- Avoid guiding testers: Refrain from using specific terms or labels present on your website or app. For instance, instead of “Click on the ‘Sign Up’ button,” prefer “Register an account.”

How is a user test structured?

A test scenario includes all test tasks to be performed by our test participants. But before we assign these tasks, we’ll give our testers two more things along the way: an explanation as realistic as possible of the situation in which they should put themselves and as plausible reason to use our product.

What is a user test scenario?

To ensure meaningful responses, usability tasks should be framed within realistic scenarios. These provide context and help testers approach tasks as real users would.

A test scenario includes all test tasks to be performed by our test participants

A good test scenario should necessarily include these three things:

- Context: A description of the situation in which the product is used.

- Motivation: A plausible reason to use your product.

- Tasks: Several, as specific as possible tasks.

How to create an unbiased user test scenario

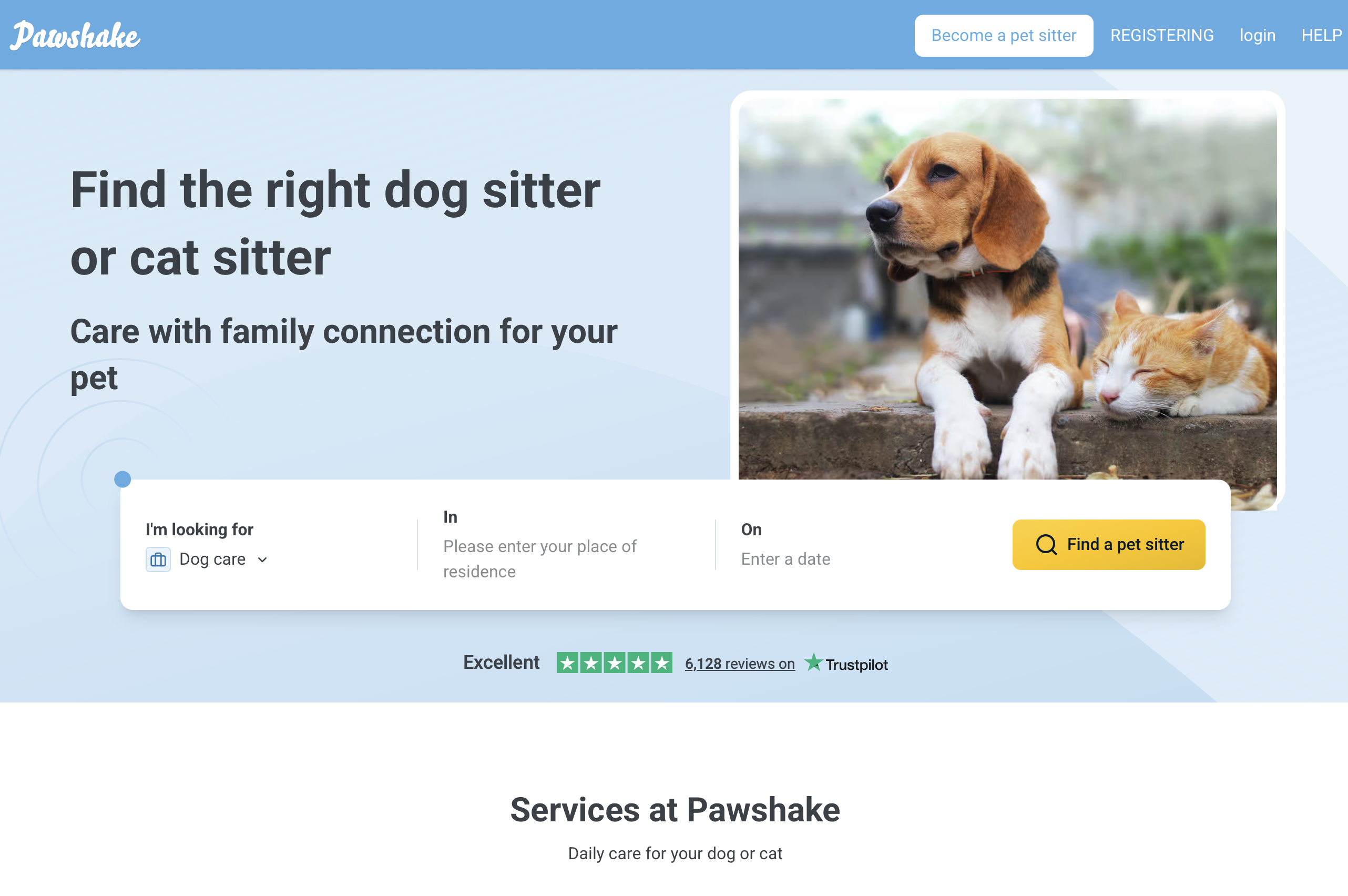

Imagine, that we'd like the Pawshake website:

On this site, users can perform the following tasks:

- Find a pet sitter

- Compare pet sitters

- Book a pet sitter

If we use these three tasks literally for our test, it sounds like this:

| ❌ Bad |

|---|

| Find a pet sitter, compare some pet sitters to each other and then book one. |

We can’t simply ask our test participants to “find a pet sitter” on this site - there’s no explanation at all why they should do this.

- Should the test participants find a pet sitter for themselves or for somebody else?

- Are they in urgent need of a pet-sitter for tonight or are they planning to go on vacation and are looking for a longer stay for their pet?

- And what animal is it all about? A cat, a dog, a lizard?

These questions influence our test participants’ behaviour.

Omitting them from our scenario risks leaving outcomes to chance and makes it difficult for participants to empathise with the situation we need them to.

If we want to observe a behavior as realistic as possible, we should be much more specific:

| 🟡 Better |

|---|

| Find possible pet sitters for your dog in your area, compare some of them to each other and try to book a suitable one for next weekend. |

This task causes your test participants to behave more naturally on the website than if you simply ask them to “find a pet sitter”.

You’re also indicating the specific kind of animal, a specific date and by asking them to find animal sitter in their area, your task becomes much more realistic.

Thus, observing a natural behavior and real usability problems becomes much more likely.

What is still missing is an explanation of why our test participants are looking for a pet sitter for their dog. We accomplish this by explaining more about the situation in which we want them to use Pawshake:

| ✅ Good |

|---|

| Imagine that you’re going to a concert in the neighboring town next Saturday and that you won’t be back home until Sunday evening. |

| For this reason you’re looking for somebody to take care of your dog during this time. |

| This is something usually done by a friend, but this weekend she has no time. However, she has told you about Pawshake and said that you would find somebody there to take care of your dog. |

| Try to find a few candidates on this website to whom you would entrust your dog during this time and compare them to each other. |

| Then choose your favorite and briefly explain your decision. |

This task already has a lot of what is necessary for a good user test.

Instead of simply asking our test participants to „find a pet sitter“ we’re also providing them with a valid reason to hire one (their friend is unavailable) and a brief explanation of the situation (a concert and a night away in the neighbouring city) to engage with the website.

Start with the Homepage Tour

Inspired by Steve Krug, a "homepage tour" is a straightforward yet productive usability testing method. It involves asking testers to explore your homepage and describe what they understand about the site.

Example of a Homepage Tour

- Take a look at the homepage and describe what you think this website is about.

- Does anything stand out to you?

- Without navigating away from this page, what can you do here?

This approach helps assess whether users can quickly grasp the purpose and functionality of your website.

5 most common mistakes when writing tasks and questions for user tests

While running Userbrain we noticed 5 common mistakes when writing tasks and questions for user tests. Here thery are and how to avoid making those same usability mistakes.

Revealing everything upfront

How do you expect your testers to deliver valuable feedback if they simply “don’t get” what your product is about?

It’s better to explain to them everything in detail right from the start so that they can start testing with a realistic expectation, right?

Wrong.

| ❌ Wrong | ✅ Right |

|---|---|

| This site targets eCommerce customers. | Explore this site for a few minutes. What do you think it’s about? |

Don’t tell people what your site is for. Allow them to articulate their first-impression and see if they understand the purpose of your site without any explanation.

Using words from interface items

As soon as you start testing something, changing what you’re testing is unavoidable.

This is known as the experimenter effect.

All you can do is to minimize this effect by trying to lead your testers as little as possible.

Imagine you want to test the following user interface:

If you’re using the same words in your task as on your site your testers will unintentionally switch into tunnel vision and hunt for exactly this wording.

All you’ll learn is how your site performs on a scavenger hunt for the wording used.

| ❌ Wrong | ✅ Right |

|---|---|

| You want to order this product now (Button reads: Order now) | Try to find something according to your taste and buy this product. |

One way to avoid this is to ensure that you aren’t priming your testers by using words that can be found in the interface of your site to describe the task you want them to do.

The way you design tasks could have a dramatic outcome on the results, without your even realizing it. In a testing situation, the participants really want to please you by following your directions. If the tasks direct participants to take a certain path, that’s the way they’ll go. If it’s not what real users do in the true context of the design’s use, then you may get distorted results.

Hearing the words your participants use to name things on your site can often be very rewarding as well. Thus you get valuable feedback if the wording used by your users is similar to yours…

Asking quantitative questions in a qualitative user test

Usability testing delivers qualitative feedback on the usability and ease of use of your site.

Usability testing is by no means a replacement for your quantitative marketing efforts.

While 5-8 testers can reveal 80% of your site’s usability problems (supposing your testing is ongoing) the sample size of your testers simply isn’t large enough to deliver significant quantitative answers.

So don’t ask your testers for their opinion, because you simply won’t get any meaningful results.

| ❌ Wrong |

|---|

| On a scale of 1-10, how easy is it to navigate the site? |

Instead, you should put your testers in the position of someone who is visiting your site with a specific goal.

It’s your job to observe their behavior while trying to achieve the goal and judge for yourself if it’s easy to navigate around the site or not.

While you can capture quantitative data like success rate or task efficiency with usability-testing, this won’t work for having people telling you how efficient they are.

How should they know?

| ✅ Right |

|---|

| You want to find an affordable hotel for your trip to Venice next month. Go on until you reach the final checkout step. |

Asking for preferred usage in a user test

Usability tests let you find out what’s clear and what’s not clear to people as they use your website.

Usability testing is in no way about opinions.

Even worse then asking about opinions is asking for a preferred usage:

| ❌ Wrong |

|---|

| Would you either search using Version A or Version B? |

| Is the feature of starring interesting? |

| Would you use this feature? |

If you want to learn about preferred usage, A/B testing is the way to go.

Setup a study with a specific, quantitative goal and compare the results of both versions.

Of course you can add usability testing and test both versions but observe people and try to spot usability errors and don’t expect usability testing to deliver data about preferred usage.

“When people express an opinion, in the course of a usability test, pay attention to it, act like you’re listening to it and taking it in. But, sort of, immediately let go of it and don’t fixate on it, don’t worry about it, just let it go. And make sure that you don’t give them the impression that you’re looking for more opinions.“ — <cite>Steve Krug </cite>

Asking about a hypothetical future in a user test

As a marketer it’s very interesting to understand the marketing funnel from people moving from visitors to leads.

So how about asking them in your usability test what makes them click?

During the last months we came over quite many tasks like this:

| ❌ Wrong |

|---|

| Would you pay for our App? |

| Would you use our service? |

| Would you subscribe to this newsletter in the future? |

Don’t ask people what they would do in the future. They simply don’t know.

People overestimate how much time they will have to use your product in the future. And they genuinely want to be nice and tell you yes. — <cite>Teresa Torres </cite>

So instead of asking for a hypothetical future, it’s much better to ask about past behavior.

You’ll learn far more understanding what triggered past behaviors of your testers than letting them imagine a fictive scenario in a nebulous future.

| ✅ Right |

|---|

| Have you ever paid for a service like this? When? Do you still use that service? |

FAQs for writing effective usability test tasks

Q: Why do usability test tasks need to be so specific?

Specific tasks create realistic user behavior. When tasks lack context-such as who the user is, what their goal is, or why they're performing an action-testers improvise. This leads to inconsistent results and makes it harder to detect real usability issues. Adding concrete details (e.g., deadlines, motivations, constraints) helps participants act like real users.

Q: Should I explain my product to testers before the test?

No. Avoid explaining your product upfront. You want to observe whether users understand your site or app on their own. Early explanations create bias and may hide flaws in your information architecture or messaging. Let users build their own first impression.

Q: Why is it important not to use interface words in the task description?

Using the same labels or phrases that appear in your UI unintentionally guides users to the correct answer. This creates "scavenger hunt behavior", where participants simply search for the word you mentioned instead of navigating naturally. Neutral wording enables authentic exploration.

Q: How detailed should a test scenario be?

A good scenario includes:

- Context - the situation the user is in

- Motivation - a believable reason to use your product

- Tasks - clear, action-driven instructions

These three elements help participants immerse themselves and make decisions like real users.

Q: What's the difference between a task and a scenarion for a user test?

A scenario sets the stage (context + motivation), while tasks describe the actions the user should take.

For example, the scenario says why they're visiting the site; the task says what they should attempt to do.

Q: Can I ask users what they prefer (e.g., Version A vs. Version B)?

Preferences and opinions are better evaluated through A/B testing or larger quantitative studies. Usability tests reveal behavior, not preference. Always observe what users do rather than asking what they think they would do.

Q: Why shouldn't I ask testers quantitative questions like rating scales?

Usability tests typically involve very small samples (5-8 testers). Ratings such as "How easy was this from 1-10?" are statistically meaningless. Instead, give the tester a realistic goal and observe how easily they can complete it.

Q: Is it okay to ask users about their future behavior (e.g., "Would you use this feature?")?

Avoid it. People are poor predictors of their future behavior and often overestimate their interest or available time. It's better to ask about past behavior or observe current behavior during the test.

Q: How do I avoid biasing participants of user tests?

- Don't reveal the purpose of the site.

- Don't use UI labels in tasks.

- Don't hint at the "correct path."

- Keep scenarios realistic but simple.

- Let testers speak in their own words and describe what they see.

Q: What is a "homepage tour" for user testing and when should I use it?

A homepage tour-popularized by Steve Krug-is a simple exercise where testers look at your homepage and describe:

- what they think the site does

- what stands out

- what actions seem possible without clicking

Use it at the start of a user test to evaluate clarity, messaging, and first impressions.

Back to homepage